The Long Take - My Conflicting Thoughts on The Bear

Why vibes aren't enough to carry a show.

Major Spoilers for The Bear, up to Season 3 (as well as The Sopranos)

One of Roger Ebert’s most famous quotes is that “It's not what a movie is about, it's how it is about it.” Meaning that regardless of how cliched a story becomes or whether it overuses a trope, critics should approach their review not with what it’s front of them, but by examining its subtleties and nuances used to express their ideas. I cannot find the original source for this line, but there’s a variation of it in a blog post, when he wrote a response to a feedback about a Hillary Clinton documentary in 2008. Still, this is perhaps the most fair approach any commentator should take into consideration.

I’ve been thinking about this, after I have caught up with FX/Hulu’s The Bear, a show in which Carmy Berzatto (Jeremy Allen White) returns to Chicago to revamp his late brother’s sandwich shop and transform it into a Michelin-starred restaurant. Carmy face a lot of challenges, from the burden of his brother’s debt to the lack of discipline in his staff, which includes the hotheaded Richie (Ebon Moss-Bachrach), the promising talent of Sydney (Ayo Edebiri), the likable Marcus (Lionel Boyce) and the ferocity of Tina and Sugar.

For its depiction of a dysfunctional kitchen, The Bear has received a lot of acclaim. On a technical level, it’s a monumental achievement; the show brings quick cuts and jaw-dropping needle drops to precise and intense effect. In terms of themes, the sense of a man returning back to his home and restoring greatness, in an effort to maintain his family’s legacy is incredibly simple, traditional and uncomplicated. For Christopher Storer and Joanna Calo, the goal is to break much of the storytelling boundaries associated with the genres it presumed to be. For them, it’s not just a show about a kitchen, but Carmy becoming the greatest chef he can be. And then there is his trauma.

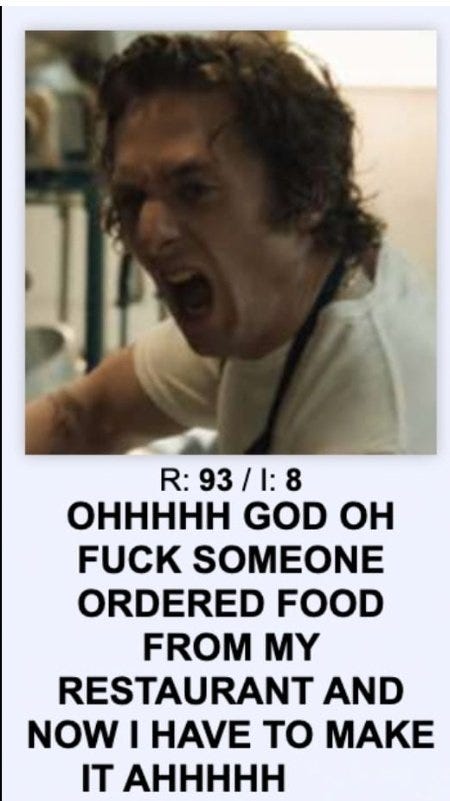

What’s particularly new, however, is the intense aesthetic. Much of this is perceived by Carmy's emotional weaknesses, shaped by his bleak experiences working in Michelin star restaurants, when he copped a lot of abuse from his boss David Fields (Joel McHale), as well as escaping his manic family. “Stressful” and “intense” are terms often uttered in reviews of the show, with the final comment reflecting on the cutthroat nature of the service industries. Everybody screams at each other, there are many extreme closeups and wide angles that look like something out of a Cassavetes film. For this, it pretty much becomes a stand-in for the show’s depth.

The Bear is in its third season, and the response has not been as ecstatic as the previous two. The criticism is pretty much exactly the kind of review that Carmy expected to receive once the restaurant had opened. The blunt of it is that almost none of the episodes drive the plot forward, the characters remain underdeveloped and that there are so many celebrity cameos it detract from the authenticity of the series. If the first season was supposed to show Carmy’s growth as a chef, then the second season was supposed to show the growth of the restaurant as well. So what was the third season all about?

I held some of these reservations all the way from its first season. As the show received rave reviews, it seems like some reviews overlook any signs of an incoherent identity. Much of the focus is on Carmy and his effort to maintain whatever’s left of the restaurant and build it from scratch. In effect, while this does make for some energetic television and great character moments, the narrative is rather shallow. Hints of any clashes between visions (Carmy’s elitist fine dining vs Ritchie’s localism) are only here and there, and there is so much technical momentum the show could have, before wondering what exactly has any of these characters learned after a series of moments where things could’ve got worse.

The second season managed to keep these problems to a minimum, delivering a rather humanist batch of episodes. The highest highs of the show have been episodes centered on the development of the characters. Marcus is sent to Copenhagen and works with Carmy’s former colleague Luca, while Ritchie is assigned to a prestigious restaurant owned by Andrea Terry, so he learns what good service looks like. The men learn a lot from their experiences; Ritchie finally possesses some self-respect, whereas Marcus’s passion for pastry increases. But they’re finally able to respect Carmy and his approach. This season has only one episode like this and it’s on line chef Tina. While it doesn’t push the plot forward, it manages to show the hopelessness of searching for a job, allowing her to be a more complex character. But the greatest quality that each of these episodes share is showing the detail of its setting and character, while mixing it seamlessly. Separate it from the context of the show, it is a masterpiece in efficient storytelling.

Still, that Season revealed some newer issues. Carmy’s romance with Claire (Molly Gordon), is underutilized, and she’s less of a character than a thin narrative device to delve into his psyche. Season Three does not return to this plot until its end, where the Fak brothers interrupt her shift at the hospital to remind her of Carmy. Too little, too late.

More prominent in the show are the celebrity guest stars. They are not the problem, so long as the performances are on point with the rest of the cast. Olivia Colman and Will Poulter play Terry and Luca, bringing some of the show’s most wistful moments and its highest points. But it can be its most middling issue and no episode demonstrates how distracting they are than in Fishes, where we meet the Berzattos, consisting of Sarah Paulson, John Mulvaney and Bob Odenkirk who are part of the family. They’re not as good as Jeremy Allen White or Colman and Poulter. More critically has been Jamie Lee Curtis, who plays Carmy’s anxious mother Donna and she is overperforming to a fault (add to the mix is Bradley Cooper playing a character in his forgotten relic Burnt). Thankfully, she dialed it down in the Season Three episode Ice Chips in which she consoles Sugar, her daughter and Carmy’s brother, as she goes into labor.

The hollowness of identity is the metatextual focus for The Bear’s recent season. It premiered with an episode that is an entire montage of Carmy’s life, following the events from the Season 2 finale and jumping from his beginnings as a cook, his departure from his family to move to New York and up his brother’s death. This is curated by an instrumental from Nine Inch Nails’ Ghosts albums. Depending on who you're talking to, it’s either a filler or a bold move. Personally, I believe in the latter. But then the structure of each episode changes. The one after that is a bottle episode, with Carmy discussing non-negotiables with the staff. Then, there’s the brutality of the kitchen as The Bear sees perfection, and midway through the season, we finally get the character centered episode that everybody likes. The rest is saturated with diverging storylines, with important information hinted at, but being put in the background while lower stakes dominate the foreground. Any scene with the Faks has been filler and I’m inclined to believe that Storer and company wants to make things light hearted to emphasize the comedy in the comedy-drama.

Much of the rapid paced editing tends to remind the viewer of previous plot points, not push it forward. Until the very end, where Carmy finally reads the very important review from the Chicago Tribune. Will this make or break him? That’s the question only the show weighs in only at the beginning and the end of the season.

The Bear is interested in exploring the roots of Carmy’s trauma further that he risks becoming unlikeable and uninteresting. But he is too tormented to be the tortured artist and too rigid to feel change. There’s one scene, however, where he reunites with his old boss David Fields, and from any perspective, it makes him a victim of the cutthroat nature of fine dining, or a feature. Either way, with Jeremy Allen White’s incredible performance, it manages to humanize Carmy and adds a new layer to his personal woes. That is, that he cannot have the confidence to control things, if he doesn’t recognise that the people around him still support his vision.

Storer and co have convinced themselves that they can forgo any traditional storytelling and they do it to a fault in Season 3. The fact that Season 3 is a stepping stone to Four, which would be the back half of an extended season gives me less hope. The Sopranos had a similar issue where the front half of season 6 is not as intense and direct as the second half. Most, if not, all of the episodes don’t lead to a particular momentum. But what it has, in contrast with The Bear, are the subtleties of character development. Tony becomes an irredeemable asshole, but there was a chance that he becomes redeemable in the first half. It enables the viewer to feel the creative possibilities of the character, but also the show itself.

If Season Four was the final season, as Ebon Moss-Bachrach predicts in an interview, it will need to pay off in a grand way that serves Carmy and everybody else better. We know enough of these characters, their strengths and struggles, that we ultimately want them to prevail. But there’s limited mileage you can get from detailing their neuroses, when the narrative is rather finite and not a lot to grab out of that. Let’s not hope it becomes a mediocrity.