Dear reader,

When critics say “art is not born in a vacuum,” they imply whatever’s in front of them is inspired by the circumstances that the creator feels is concrete. Since we also have to put ourselves in their shoes, we also have our interpretation based on individual experiences that form or flatter their perception of the world. That’s probably why in the world of cultural criticism, you’ll find the author spending a graf or so about how the thing they’re reviewing is close with whatever current events are nearby.

Once Donald Trump got elected, people latched on the Arrival because it reminded them of immigration. People wondered if, in Hell or High Water, the outlaws trying to prevent foreclosure of their ranch would be the Deplorables who will vote for him. Whenever a riot occurs over a black man being choked to death by a cop, Do The Right Thing is brought up repeatedly in articles and instantly recommended on streaming services. Not just because the events of the film and reality mirror each other, but because it is a sociological masterpiece of how people, at their angriest and certainly not in the most relaxed day of the summer, view each other. Other films, like Strange Days or Battle of Algiers, are revitalized to remind readers that it wasn’t the first time they’ve witnessed a crime in real-time and that film is derived from those events to make them more palatable. Films from black directors and writers are treated with listicles when police brutality occurs and demonstrating that society had played fiddle to a community already having it worst for decades, and no one has done anything to mitigate it.

This way of thinking isn’t inherently terrible. The point of art is to serve as a reflection of societal trends. But it does reveal the possibility of criticism to wedged in cheap political slants, just to score points that are anything besides ‘you’re just on time.’

When lockdowns were globally implemented, a lot of people rushed to pieces about Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion, released nine years before the pandemic hit. It became a big streaming hit on Netflix. Many noted that the roles there are parallel with doctors working day and night to get the vaccine ready, WHO officials getting caught in an international crossfire and conspiracy bloggers who take alternative medicine so that they can flip the bird at the establishment. Others follow suit by watching, writing, and listing movies about the pandemic to remind people about the epidemic, like Outbreak, 12 Monkeys, and The Omega Man.

Then there’s the category of likening the thing to the pandemic. People seek to watch and write about The Lighthouse because they feel that Willem Dafoe and Robert Pattinson trapped in a lighthouse for a long time, will be similar to that of a tight lockdown. You feel isolated, imprisoned and eventually, demoralized by your supervisor.

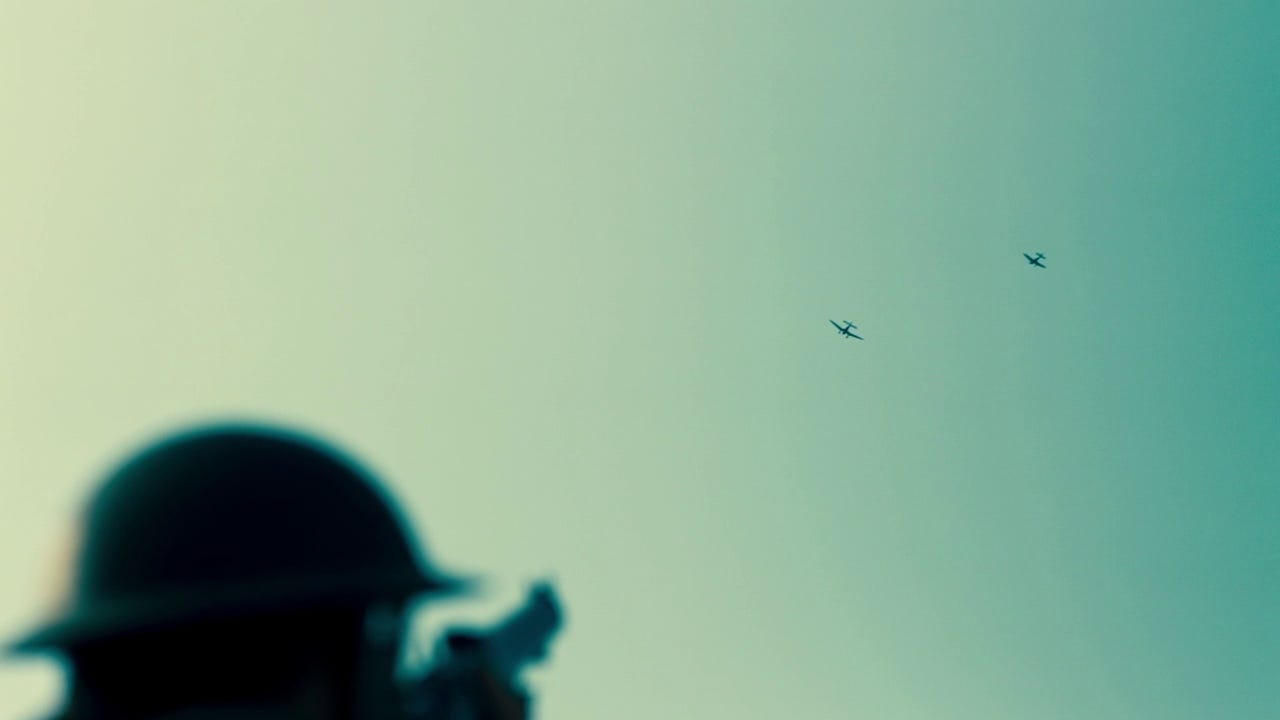

So here’s me participating in this mentality now, having been concerned about being isolated for more than four months. The movie that reminds me most about the current pandemic is Dunkirk. While it’s about the Battle, Christopher Nolan eschews typical war tropes, allowing him to demonstrate the human mind at its most stressful, a feature that’s omnipresent in his filmography. It stands out as one of Nolan’s most experimental efforts because he sidesteps much of his worst tendencies, like excessive exposition, and automatically writes protagonists drifting towards burden that makes them supposedly deep. There are no individuals with distinguishable traits, but the soldiers we witness have one function: to escape from the Germans, all of whom are unseen. Clocking in at a tight 108 minutes, Dunkirk tells the Battle in three layers: the land in which the Allied soldiers try to leave, the civilians trying to rescue them out to sea, and the dogfight between several spitfires above the ocean.

Comparing a pandemic to war can only make sense in terms of instinct. People make that analogy all the time, from Presidents to writers, because it implies that nations are attacked for their indemnity, without assessing how much collateral damage there is. But it’s understandable to respond like this where there is so much uncertainty. As you watch Dunkirk, it’s a war movie in the least conventional sense. You cannot see the enemy, and it strips much of its power. Much like the virus, it does not discriminate against any other soldier, except for the fact they’re either French or English. In particular, one Frenchman, who followed wherever the mole went, is held at gunpoint by a platoon for being a traitor, as the Germans shoot them). In effect, the characters’ anxiety is emphasized more than military strategies.

In Dunkirk, we learn that civilizations can free themselves if their people possess the duty of helping others in a crisis. It’s when Commander Bolton (Kenneth Branaugh) utters the word ‘home’ when a fleet of boats arrive to rescue the soldiers. The same can be said when Mr. Dawson volunteers in this effort to avoid the paternalistic scrutiny from the Navy using it to fight.

But human nature can prove to dent trust between the traumatized and those who are now caring for them. Cillian Murphy, in a flashback, is seen commanding a rowboat of soldiers. When Mr. Dawson saves him, he panics about returning to land. It would be simple to say that he’s afraid of going back to Dunkirk, but note that the soldier has lost a sense of authority and duty as a fighter.

The pilots manning the Spitfires retain whatever honor they have. And where the metallic, empty serves a new form of Hell, the pilots earn more dignity after defeating the enemy. The fallen cheer for them, because they are most important in defending them during a crisis.

Once Dunkirk came out, some took the opportunity to compare it with the nationalist-populist paradigm so concurrent in our global politics. In The New York Times, Manohla Dargis raved the film as “a characteristically complex and condensed version of the war that is insistently humanizing.” Oddly, Dargis concluding that “you are reminded that the fight against fascism continues,” which may be about Donald Trump or Brexit. (The flip side of this coin is Brexiteer Nigel Farage, who “urged youngsters to watch Dunkirk” on Twitter). Ultimately though, it’s about the British spirit and why, in making the characters anonymous, it prevails in demonstrating its self-reflexive romanticism and stoicism.

Dunkirk deduces from isolation, danger, desperation, fear, relief, and extremely bodied need and effort. Those aren’t my words; they appeared in Dargis’s review, and these are the words you’ll be thinking during a pandemic or a riot. Metaphors, mainly of two events with more significant consequences, only help enhance the perception of what is going on, despite its unequal equivalences. What I’ve learned following Christopher Nolan is that he doesn’t end his characters’ journey in misery. Instead, it keeps finding another way to go through or steer clear away from the angst. Analogies are drawn to art because that is one way we can respond to them. And that may be the only way to make the situation plausible. Because ultimately, we live in a society.

Thanks for reading!