Anti-Woke Directors and Their Magazines

The last time I wrote about a director being on the cover of the magazine not for their new films, but when they are commissioned to pen an essay was when Martin Scorsese wrote about Federico Fellini at Harper’s. A lot of people had a lot to say about it - that he made a small, but vocal critique about content in the streaming era - but there’s no denying that Scorsese has a huge passion for the medium and the magnitudes that Fellini had inspired him.

There are two other filmmakers, whose name was on the cover of a magazine: Bruce Beresford in The Spectator Australia, and David Zucker in Commentary Magazine. They both contributed pieces about one thing: feeling detached from a world that has gone incredibly progressive.

Bruce Beresford is one of Australia’s most accomplished filmmakers. He has made several films that have seen the industry flourish since. It would include Breaker Morant, Don’s Party and The Adventures of Barry MacKenzie, which introduced us to Dame Edna. But he’s most notable for directing Driving Miss Daisy, which won several Academy Awards including Best Picture and was very controversial because of its depiction of race (and that the more superior film released that year Do The Right Thing, was snubbed). David Zucker was behind Airplane!, The Naked Gun franchise, and was behind the landscape of modern spoof movies, which included Scary Movie 3.

Beresford wrote in the Speccie’s diary titled Woke Diary, although the headline doesn’t paint the broad picture of the piece. The Diary is the magazine’s feature where we read the first-hand mind of the author, whether it would be a scientist, an actress or anyone else, and see how they respond to current events or their job. Hence the first paragraph begins with this:

The Covid lockdown has confined me to the house for long periods. My wife is downstairs working on a new novel. I’m upstairs working on film scripts. Often days go by when we meet only in the evenings, though I sometimes phone her and suggest we have lunch together on the verandah. I have spent most of the lockdown either writing scripts or else working with American writers, emailing notes back and forth and having interminable Zoom calls. A proposed film about Buddy Holly seemed to be all set to go into production when my Los Angeles agent had a call from a producer (who chickened out of contacting me directly) with the news, ‘We’ve decided we want a black director’. I pointed out that Buddy Holly was not black, that I had spent a year working with the writer and had done a huge amount of research. The response was that the decision was made because a key part of the script featured a rock tour Holly made with black musicians. I suppose I could’ve claimed Aboriginal ancestry, a popular move these days, but, on reflection, decided that a legal tussle with studio lawyers would be interminable and absurdly costly.

Nothing out of the ordinary for Bruce, or for that matter, an anti-woke critique, but here are a few fine facts. He has directed a film in 1986 called The Fringe Dwellers, which is about an Indigenous Australian woman yearning to move out of her family camp, that is on the fringes of an Australian society that is dominated by Whites. It was really popular at the time of its release, and given that the Australian commentariat isn’t as strongly opinionated as the Americans when Driving Miss Daisy has won, you can understand where he is coming from. Speaking of Driving Miss Daisy:

Nearly twenty years later I applied again, this time believing that having directed a film, ‘Driving Miss Daisy’, which won the Academy Award, I naively imagined my celebrity status had made a leap forward.

I notice that Driving Miss Daisy is the standard for acceptable movies about racism that tries to play it safe by avoiding the tendency to alienate their (white) audiences. The Wrong Movie Won, but making matters worst is that The Wrong Movie With The Wrong Way Of Telling It won over The Right Movie That Wasn’t Nominated, therefore the system is operationally corrupt.

Meanwhile, from October 2021, David Zucker was asking why we are losing our humor, in a piece that’s part of a symposium of wokeness featuring the likes of Bari Weiss and… yeah, that’s it. It has been a contentious topic to ask whether we cannot laugh anymore, because of the intolerance of social justice warriors that run the entertainment sector. To summarise his point of view:

Comedy is not dead. It’s scared. And when something is scared, it goes into hiding.

This is a sentiment that rings true if you have grown out of comedy or found it not to be as funny as it was. Even comedians are willing to self-censor, in order to get superficial clout. The evidence that could back Zucker’s claim would be many such cases, but the most recent one I can think of is the neutering of Ethan Klein, a YouTube comedian who made really edgy jokes with the N-word, disowned an interview he did with Jordan Peterson, after realizing that he may have caused misinformation about COVID-19 and trans people.

Beresford’s essay didn’t make waves (mainly because The Spectator Australia has a rather smaller audience, compared to its British and American counterparts), but Zucker’s comments did cause a news cycle, experiencing the typical responses of OK Boomer and “I’m not going to watch your movies anymore”. But in some way, he serves as an authoritative voice for comedy in the way that Dave Chappelle does. Zucker and Beresford have reached a point where their opinions against orthodoxies and cancel culture do not hurt any more opportunities. They have achieved and changed so much of the cultural landscape, that part of it will shift into more radical notions as time would pass.

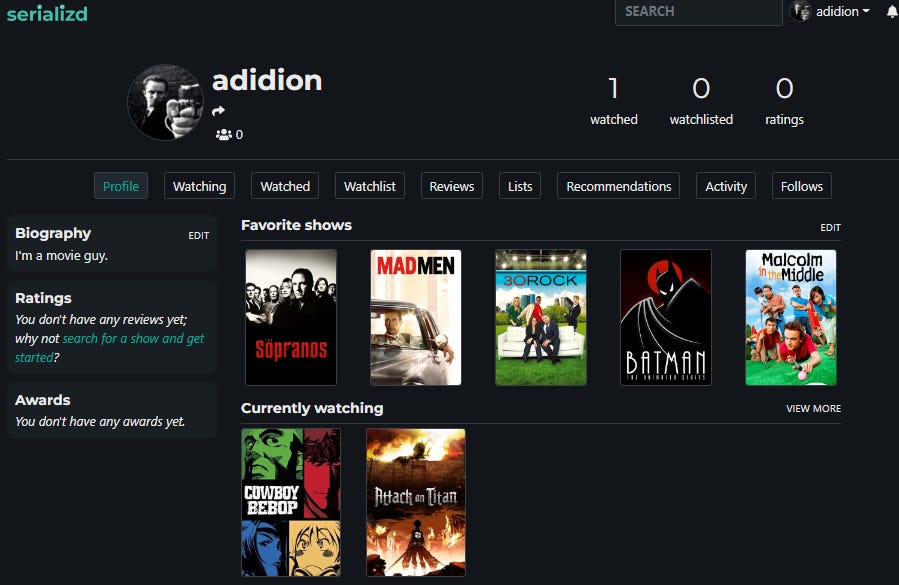

Letterboxd, but for TV

The guys behind Letterboxd have brought you the same platform, but for TV. It’s called Serializd, and it has all the familiar features: you can log in TV shows you watched, log in episodes and seasons, before listing them out. I already opened an account, just in case I need to update what shows I’ve been watching, so if you want, you can follow me on there.

My first impression, upon hearing about the app, is not of what it is, but what it can be. Let’s put aside what needs improvement; mainly that it doesn’t have a tool that properly logs in a TV show that made me use Letterboxd properly. The last time I wrote about Letterboxd, it was mainly a personal anecdote of using it, and what it has become:

For what it’s worth, Letterboxd has been a very useful website to keep track of all the movies you’ve seen. The list-making is incredibly fun, and I feel a bit of catharsis writing a few capsules here. But to wax nostalgic just for a little bit, there was a time when the users came around organically when the site first began in 2011. It wasn’t a site that is now, I think, mostly reserved for Tumblr and Twitter weirdos who happen to like film, or when they need more than 280 characters to vent. The most popular user was a guy with a Le Samourai avatar, and he would log in 10,000 movies and exhaustingly go into detail about his feelings about them. So was some Dutch guy named DirkH or Todd Haines. I used to follow these people, and in my humble opinion, the community was much smaller and because of that, it was far more interesting.

And the last time I mentioned Letterboxd in this newsletter?

While Letterboxd maintains “reviews” that are either unfunny one-liners or pretentiously overwritten blurbs,

Serialzd has the potential to be as big as its sister site, and the main driver would be its culture. Will it bring in the same annoying users like Demi Whatshisname and David Ehrlich? Are there going to be didactic Marxists rambling about The Sopranos’s critique of capitalism? I don’t know, but every platform will start with the intuition, to borrow from The Social Network, that they don’t know what it will be. All they know is that it is cool.

Movie of the Week: Superbad (2007)

I lost count of how many times I have watched Superbad. I was a teenager when I first saw it, and there are many jokes that are etched in my mind and McLovin. Upon further viewings, I knew that it held up not just as a coming-of-age film, but as an exploration into a typical rite of passage: three (well two) unpopular nerds are given the privilege by their crushes to come to a party, with the condition that they bring alcohol. This gives the boys an impression that they can finally score, before heading their separate ways to different colleges. Watching it for the umpteenth time. I realize that the three characters are uncertain about themselves in the lead-up to the party. There are frequent references to protected sex, which Seth rejects with the excuse that it wasn’t part of a “plan” (we see that by the end, McLovin actually came well-prepared) and consent that is littered across the film, but it’s barely preachy.

Speaking of which, McLovin is not simply the best character here, but also the most important, because he embodies much of the boyhood we come to expect in different movies. He overestimates how cool he is, is fearful when the worse has happened (like being asked for his fake ID), but comes to the middle ground by hanging around a duo of police officers who do feel less insecure when he’s around him. Superbad, is structured like an epic: the first act is set at a high school, then we get to the liquor store, later a college-aged party and in-between, hanging out with the cops, and finally their party. It is, in my opinion, the Lawrence of Arabia of party movies.

ICYMI: Film Club with Hannah Long

A while back, I had the pleasure of talking to Hannah Long, a freelance writer and editor, who has been published in the defunct The Weekly Standard. I ask her about how to make movies more accessible to a wider audience as a culture writer. Then we proceed to talk about Logan Lucky and why it is the best film of Appalachian America. Here’s an excerpt:

LoT: Much like my last guest at Film Club, you gave me a long list of favorite movies, and Logan Lucky stood out among the rest as the most recent. So what made this your all-timer?

HL: Growing up in Appalachia, you tend to feel rather invisible in pop culture. So I'm always happy to see people "from around here" (a phrase I'm using broadly, since while the characters are West Virginian, the movie takes place in locations adjacent to but not in Appalachia) who aren't just unsophisticated morons. In this, quite the opposite, they outsmart the big city sophisticates. I suppose there's some wish fulfillment involved here. So many stories about Appalachia are about how miserable we are. We're more Dickens than Dostoevsky, thank you very much! A heist movie is by definition about fun and glamorous people, not the miserable suffering masses. It feels very ennobling for such a story to be set here.