Film Club: Matthew Continetti/Sweet Smell of Success (1957)

The author of 'The Right' talks about the current state of American conservatism before diving into one of his favorite films Sweet Smell of Success.

Welcome to the Lack of Taste Film Club, where we will talk to non-cinephiles and cinephiles about the movies that they love. You will find a different flavour to Film Club entries going forward. Instead of going straight to discussing the movie being chosen, we want to get to know the guest more. A general Q&A will come first, movie comes second.

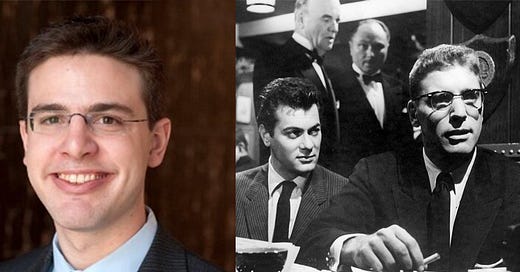

In this edition, I spoke with Matt Continetti, the author of The Right, a broad overview of American conservatism starting from 1922 all the way up to and after Donald Trump. Continetti has been involved with the conservative movement, and he documents its roots in a more detailed and detached way that only he can. He was also the founding editor of the Washington Free Beacon and is a Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. We talk about the book in more detail, from the responses to the reality of movement conservatism today. After that, we dive in to one of Continetti’s favorite films, Sweet Smell of Success.

Let's say someone read The Right and fits precisely into the profile of a Trump voter. Not just any layman who would vouch for the last Republican president. But claim that the conservative side of the establishment is weak and should be abolished and that Trump won the 2020 election fair and square. What are you hoping that reader would get out of the book?

My hope is that the reader you describe will get the same thing out of The Right that any reader would. My book is a historical survey of U.S. conservatism over the past hundred years. I wrote it to provide a baseline story, a common field of reference, for understanding the American Right in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. I want readers to know what the Right was like before the New Deal, how it came to think of itself as "conservative" in response to FDR's domestic and foreign policies, how it changed its orientation toward foreign intervention after World War II, and on and on, up until January 2021.

The book has plenty of material for readers of any political persuasion to learn from and mull over. And I have been gratified (and a little surprised) by the positive response the book has received among people who do not consider themselves part of the Right.

And I have found that some Trump supporters do not like the book. Why? As far as I can tell, it’s because I am critical of Trump's personal behaviour, especially after the 2020 election, and somewhat sceptical (though I try to be detached and dispassionate) at the long-term prospects of this latest "New Right." Another reason is that these critics identify me with a sector of the Right that they have long opposed. They read the book as an apology for the domestic and foreign policies of George W. Bush. I disagree with their interpretation. And I prefer it when critics review the book I wrote rather than me personally.

What the reader won't get from The Right is a false opinion that Trump won the 2020 election.

Following the Dobbs decision, do you think that all of the existing ideological factions within the conservative movement would be grateful for having at least one victory that they could share after the Soviet Union?

The Dobbs decision was a victory not only for the pro-life movement, but also for the conservative legal movement. As I recount in The Right, the conservative legal movement has worked for several generations to reorient the Supreme Court toward an originalist interpretation of the Constitution. Justice Alito's decision in Dobbs is a classic example of originalist jurisprudence. And one of the reasons for the conservative legal movement's success is that it unites social conservatives and economic conservatives, as well as legal elites and grassroots populists, behind a common project of reviving the Founders' Constitution.

Not all economic conservatives and national security conservatives agree with the aims of the pro-life movement, however. Dobbs was a triumph for a conservatism that works through institutions rather than against them. But it may lead to dissension within the ranks of the Right.

I notice that social media seems to be underplayed in the book. I believe it is a fundamental aspect in the evolution of not just the movement's media entities, but shifted the core of the movement’s mission. If it wasn't for YouTube, Twitter or Facebook, then the likes of Ben Shapiro, James O'Keefe and Andrew Breitbart wouldn't have emerged. Donald Trump's Twitter feed was essential for his success, and overall, Big Tech has been the newest form of the culture wars where conservatives feel they are marginalized because of the biases they face from these platforms. But they are now more skeptical of corporatism. Do you think it's fair to say that as it evolved from magazines to talkback radio and cable news, that technology is harder to escape for conservatism?

No doubt social media is important in the formation of today's Right. I discuss Donald Trump's relation to social media in particular in my book. The technology companies and their products raise a whole bunch of issues for both Right and Left, from viewpoint diversity to childhood development to monopoly power. We need to think through all of these challenges carefully, empirically, sceptically, and realistically, especially when someone argues that the heavy hand of government is the solution.

I am not sure that conservatism's problem today is a lack of platforms. Relative to where the conservative movement began after World War II, conservatives are more prominent in political discourse than ever before. What worries me isn't the medium but the message. I am more concerned that the Right has lost its moorings, that it has drifted from the principles of constitutionalism and limited government, and that it is forgetting the tradition of freedom at the heart of American conservatism.

I've seen good reviews on The Right overall, but have you read any critiques and what was the one that you felt was the most legitimate and fairest?

I thought that Timothy Shenk's review in The New Republic had some good lines. At one point he describes me as looking like MSNBC anchor Chris Hayes's Republican cousin. I laughed. Shenk co-edits Dissent and writes from a left-wing perspective. The critique from the Trump-friendly Right that I thought was most perceptive came from Daniel McCarthy in First Things.

Of course, they are both wrong. The book is flawless. All of your readers should buy at least one copy.

I live in Australia, as you should know, where the foremost centre-right political party, the Liberals have massively lost this year's election following nine years in power. (I write about it in great detail about how it was an unhappy period). At the moment, there is a leadership contest for the Tories, now that Boris Johnson is out of the picture. The Right is about not just any right-wing, but the intellectual strands of American conservatism. The Australian conservatism that I live in is more pragmatic than ideological and barely has any similar debates compared to what the US has. What can we learn from the current state of conservatism over in America?

In 1999, David Brooks wrote an essay for The Weekly Standard magazine where he described a visit to Australia that made him grateful for U.S. conservative activists such as Paul Weyrich. Brooks tells of panel discussions in Adelaide where conservatism was treated "as some abstract menace that afflicts people elsewhere, like smallpox." According to Brooks, the situation is different in America, where figures like Weyrich built institutions that forced conservative ideas and positions into the public square. The movement conservatism found in the United States is more "ideological," more religious, and more populist than conservatism elsewhere.

Skimming over Brooks's piece, I couldn't help thinking that today American Progressivism is just as closed off to conservatism as those Aussie intellectuals were decades ago. Why? A large part of the reason is the radicalization of the American Left over the last decade. But I also think that over the same time span the Right has become less attached to ideas and more attached to attitudes ("Drain the Swamp") and to individuals (you know who). Maybe these two changes are related.

I'm biased, I know, but I happen to think that American conservatism is as exceptional as America. We need a conservatism that defends the American tradition of liberty and the social institutions that cultivate the self-discipline necessary to sustain freedom. We need a policy agenda that encourages strong families, religious liberty, safe communities, steady work, and peace through strength. It's a tall order that requires confident, consistent, and effective leadership. We're having trouble finding that leader.

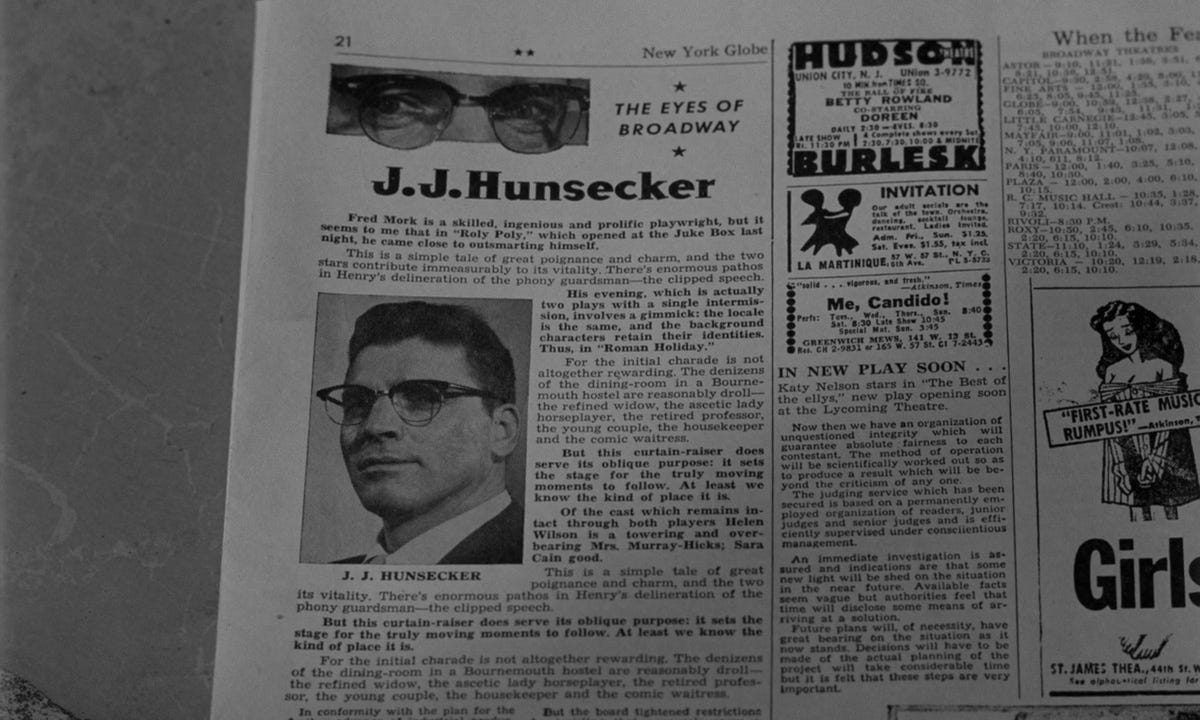

There have been two great movies about journalism released in the 1950s: Ace in the Hole and Sweet Smell of Success. The former deals with the direct relationship between the press and the truth, but in the sense that it advances the reporter's career at the expense of the subject. Sweet Smell of Success is about a famous columnist JJ Hunsecker (Burt Lancaster) using his connections to ruin his own sister, because he doesn't like her boyfriend. This involves press agent Sidney Falco (Tony Curtis) who is about as conniving as JJ Hunsecker. So as a journalist, what do you find special about this movie in the sense that it says something significant about your profession?

You left out the other main character in Sweet Smell of Success: New York City. I think the first reason I respond to the film is its depiction of New York—the locations, the street scenes, the faces in the crowd. The New York where I lived from 1999-2003 was richer and more technologically advanced than the city in 1957, but the vibe was the same. Still is.

I wrote political profiles and feature stories before I moved into opinion journalism and historical writing, so I don't identify with either Hunsecker the gossip columnist or Falco the press agent. But I did edit a website for eight years that has a reputation for "combat journalism." What the film does well is communicate the activity of journalism—snooping for news, trading favors, cultivating sources—as well as the power that media has to create and destroy reputations. There's a great moment when one of Hunsecker's competitors tells Falco (I'm paraphrasing), "I might have a bilious personal life, but I run a decent column." Many journalists would benefit from that sense of self-awareness.

Both JJ and Sidney Falco seem to share a casual paternalism on Susan Hunsecker (Susan Harrison) who is, at all times, a pure and innocent person in this mess. One of the accusations planted against Susan's jazz-playing boyfriend Steve Dallas is a marijuana-smoking communist. You would think, in the grand scheme of things, this wouldn't be a newsworthy story until you sprinkle it with trendy targets that sensationalize the nature of it. An interesting thing about Clifford Odets, one of the screenwriters, was that he faced the HUAC hearings and in doing so, expressed regret. You can certainly sense an autobiographical layer to it. Do you feel that it's pretty truthful on Odets' part?

You are right about the brilliant writer Odets. But I'm not sure how closely he identified with Dallas, who strikes me as naive and unable to play the game that Hunsecker has mastered. I also don't know how innocent Susan is. She (SPOILER ALERT) breaks up with Steve, then turns on Falco after he rescues her. One of the themes of the movie is that nobody is pure. Everyone is trying to manipulate everyone else. That's the only way to get ahead—or survive.

Much like Glengarry Glen Ross, which I discussed with Matt Labash, the star in this movie has a really quotable screenplay. What are some lines that you come back to?

There are so many. "Watch me run a 50-yard dash with my legs cut off," Falco tells his long-suffering assistant before trying to get back into Hunsecker's good graces. Later, Falco complains that Dallas suffers from "Integrity. Acute. Like Indigestion." Toward the end of the film, Falco says, "I'm going home. Maybe I left my sense of humor in my other suit."

Hunsecker has my favorite lines. "My right hand hasn't seen my left hand in 30 years," he tells Falco. At another point he says to Falco, leering, "I'd hate to take a bite out of you. You're a cookie filled with arsenic." But my favorite line has to be after the first scene at restaurant 21. Hunsecker and Falco are outside on the street. Amid the traffic, a bouncer ejects a drunken patron from a nightclub. Hunsecker takes in the scene and announces, "I love this dirty town." That's the way I feel about New York.

The dazzling black-and-white cinematography was created by James Wong Howe, who shoots New York City like the noirest of noirs. Any great shots you think about?

The opening montage of newspaper production and delivery contains some wonderful images. I love the deep-focus shots of groups in restaurants, nightclubs, and diners—they remind me of John Ford. But I think my favorite shot appears during the confrontation between Dallas, Susan, Hunsecker, and Falco at the theater where Hunsecker's television show is produced. It's a wide shot: Dallas, Susan, and Hunsecker argue in the foreground while Falco paces in one of the rows of seats in the background. The camera holds as the debate continues and Falco exits the frame. Then the camera pans with Hunsecker as he moves in the same direction as Falco, who is now sitting. As Hunsecker takes out a cigarette, Falco leaps from his seat to light it. The timing is perfect. The relationship between the two men—both how they relate to one another and how they want to appear to others—is communicated instantly. Not a word needs to be said.

How do you interpret the ending, cos I think it is brilliant. Susan screams at JJ for ruining her life, and Sidney Falco attempts to escape, but only gets beaten by a bunch of guards as the sun literally rises from New York. If that isn't how you conclude a film, I don't know what does.

We are left with the impression that the characters are changed forever: Susan will leave, and Falco has been expelled from Hunsecker's circle. As I think about it, though, I wouldn't be surprised if Susan ended up coming back and Falco and Hunsecker worked together again. None of these characters can be trusted, but they also are co-dependent. None would be able to exist without the others. They aren't likable people, but they are eminently watchable. Reminds me a lot of Washington—but with better dialogue.