Film Club: Matt Labash / Glengarry Glen Ross

The former Weekly Standard journalist discuss about his prose, the decline of magazines before diving in to the most quotable David Mamet film.

Welcome to the Lack of Taste Film Club, where we will talk to non-cinephiles and cinephiles about the movies that they love. You will find a different flavour to Film Club entries going forward. Instead of going straight to discussing the movie being chosen, we want to get to know the guest more. A general Q&A will come first, movie comes second.

In this edition, I spoke with Matt Labash, a former National Correspondent at The Weekly Standard. This is not the first time I have spoken to someone associated with the defunct magazine, but I have been meaning to talk to Labash ever since I launched Lack of Taste. Labash is part of an old blood in journalism; someone who has written for print magazines and has acerbic prose that bounces around the wall like a party banshee. I asked him about the decline of magazines, particularly the male lifestyle genre, before diving into one of his favourite movies Glengarry Glen Ross.

So what have you been doing in between your Substack and the closure of The Weekly Standard?

Well since launching Slack Tide as some call it, because that’s what I named it, I’m holding on for dear life. Having your own thing demands a bit more frequency than I was used to with my once-a-quarter or so clip at ye olde mag. We print magazine types used to require a lot of time to select stories, report stories, and prayerfully meditate over stories. Which basically means we went out to lunch a lot while procrastinating. But in between The Weekly Standard and Substack? I was pretty much Dustin Hoffman in the pool in The Graduate. Just drifting. Except I don’t have a pool. Nor was I bonking older women like Mrs Robinson. Unless you count my wife, who is a few months older. But she’ll likely divorce me if we do that, so let’s not. I did some writing for everyone from the New York Times to The New Republic to The Spectator to The Drake (a fly fishing magazine) to you name it. But not so much writing that I didn’t take lots of time to fish and kayak and chop wood and cook and walk my dog through the woods and that sort of business – the business of life. Sadly, the business of life doesn’t pay very well. And I have two college tuitions breathing down my neck. So after a couple of years of that, I went back to work in a more vigorous fashion. Though I still do the rest, as well, because a person has to stay whole. Just not quite as much of it.

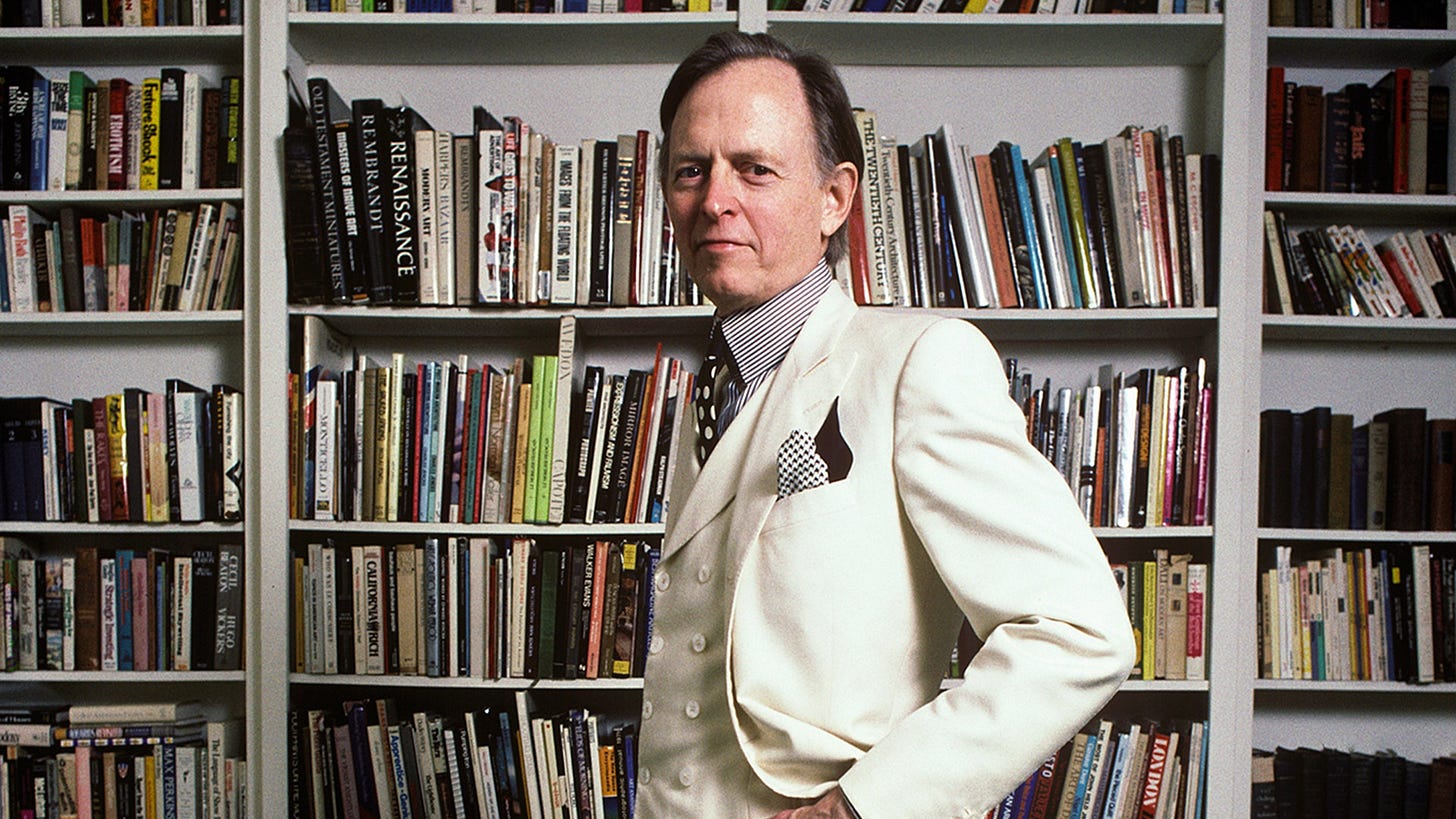

I’m hoping that you could clue me into the manner in which you style your prose because it strongly reminds me of Tom Wolfe. If someone asked how could anyone write like you, what would your advice be?

Well thank you kindly, but my advice would be not to. I mean, I too, love Tom Wolfe, don’t get me wrong. I’ve read just about every word he’s written and probably wanted to be him when I was 22, minus the ice-cream-man suit and spats. His attention to the telling detail was second to no one’s, and he was a prose pyrotechnician, besides. The dude could write about grass growing and make it interesting. And he had great story sense – as in what made one. But after you read those journalism collections of his, which are all wonderful, and you decide you want to be Tom Wolfe, and start laying it down, you realize how utterly futile it is to imitate him. Because there is and could only ever be one Tom Wolfe, and he died in 2018 (with his spats on, I’m guessing). I can’t pull off onomatopoeia and multiple exclamation points, and wouldn’t want to. Not that that was the meat of his writing – just some of the distracting accents. Kind of like drugs was for Hunter Thompson, whose most interesting writing often had nothing to do with drugs. In fact, drugs were maybe the most boring part, save some chunks of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. But my larger point is that you ultimately have to sound like yourself, or it’s not worth doing. If your voice is worth hearing, write in it. Fully inhabit it. If it’s not worth hearing, then get out of the business and find something more stable to do like base-jumping or child soldiering, since journalism is in a perpetual state of collapse anyway. Especially the written version of it. But you can’t build a real writing life on imitation. It’ll never work. It might be useful to find good people to steal from when you first get started, just to find your rhythm. But ultimately, you have to find your own rhythm. If you don’t, you’ll be found out as a fraud, and it won’t be very satisfying, anyway, to be voicing someone else’s thoughts or mannerisms.

Incidentally, while we’re talking Wolfe – and I wrote this up a few months ago in a piece I did on writing on my own site – but I met him once, long ago in my twenties. We were at the same dinner – he was the guest of honour, I, then as now, was just a mope. I promised myself I wouldn’t slobber all over the poor guy if I met him. Wouldn’t want to mess up his suit. But I was pretty deep in my cups once I encountered him. And it just came out, almost involuntarily: “Mr Wolfe, I need you to know, whenever I have trouble getting it up, writing-wise, I just read something you wrote like ‘The Last American Hero,’ your story about {the stock-car racer/moonshiner} Junior Johnson, and it’s like an adrenaline shot to the ‘nads.” I embarrassed myself. And him, I’m sure. But he was his usual courtly Virginia-gentleman self, and generously offered: “You know, I do the same thing when I’m in that spot. But I read Henry Miller.” I liked that answer a lot, as Henry Miller is a pretty good adrenaline shot, too.

You often write about political polarisation in America in your newsletter and how almost everyone succumbs to their own Metaverses, where they are the heroes of their own story and, to quote from The Dark Knight, live long enough to become villains. From my personal experience, I know some friends, who delude themselves into their own ideology, that they rarely get the chance to sit down and relax, and eventually rot into horrible human beings. What would you usually do to avoid that character arc?

I would say that we all, of course, have our political predilections, our biases, and our pocket list of villains we think to deserve to die slow, painful deaths. That’s natural. But our politics, held onto too tightly, inevitably ruin just about everyone. If you can never hear the music, or appreciate the humanity of the people you disagree with – and they almost all have something to recommend them, whether you’re a foaming-at-the-mouth Trumpster, or some tight-assed faculty-lounge wokester – you’re gonna miss out on the full human experience. You’re gonna live in your cramped, filthy hovel of a world with grievance and anger and resentment, which ain’t gonna affect your ideological enemies very much, but it will eat up your insides. So my advice would be to get outside. Both physically – in nature, which is a balm – and outside yourself, as well. Your crap never smells as good as you think it does. So smell somebody else’s on occasion. Read other things besides political BS. My reading diet spans lots of subjects – I very rarely read straight-up political books. Because political life, as currently practised, is death. You can only take so much of it, and stay healthy.

I love magazines. For me, buying a print issue is like buying a comic book. You wrote an op-ed in The New York Times about the substantive decline of men’s magazines, around the time when GQ had a special issue about being a man, which nowadays is hardly traditional. I find the genre of men’s magazines fascinating because, in its heydays, they often border on acceptable tastelessness. I remember when GQ used to run scantily clad covers of female celebrities, but not anymore. Esquire used to have a “Sexiest Woman Alive” feature every year, but now their main attraction is a left-wing blogger. Every article from those outlets always has to conform to the celebrity’s ego, rather than permitting the reader to appreciate the beauty of these people, because that’s clearly part of their personality, alongside whatever talents they have. The writing back then was tolerable and wasn’t all about spotting potential crypto-fascists. How the hell did it come to this?

Sorry man, I hate comic books. But I’m with you otherwise, brother. I miss hot supermodels and overwritten stories on all manner of subjects. Magazines were almost……aspirational. You were entering another world. I still subscribe to them out of lifelong habit, but I barely feel like I need to check in anymore. Unless I aspire to be some neutered house pet policing actual writers for using the wrong pronoun, while body-positive editors assure me that I should be attracted to 300-lb models in groaning yoga pants. It’s all a stupid scam and isn’t fooling anyone. Except maybe the people who work there, and I doubt even them. The last gasps of a dying sphere. The world is often a sad place. And magazines have become an even sadder version of an already sad place. I mean the ones that still exist – because many have ceased to exist. Or else they’ve cut back their publication frequency so much, that they might as well go under. And I don’t say any of this with joy or smugness. I say it with deep and genuine sadness. Because I, too, have always loved magazines. Many of my favourite writers came out of them. And I worked in them for most of my life. Still do, sometimes. Magazines were once a great place to do work that had immediacy, but with 360-degree vision and without the straitjacket that newspaper writers often have to wear. (And newspapers too, except for a few of the majors, are mostly dying.) Magazines also used to feel like they had greater carry than what happened in the online world. But that distinction has been almost completely eroded. There are people who work for storied print magazines now (The Atlantic, The New Yorker), and who still do great work, but who almost don’t care if they get in the print version of their own magazine. Because if it’s not online, it really doesn’t exist. Posting your story and then ringing the social media bell is really all that matters now. I’m still not on Twitter. But I am a lonely salmon, swimming upstream on that one. And of course, I don’t begrudge people for getting my stuff out on there on Twitter. In fact, I appreciate it. Because I’m a total hypocrite, as well. Here’s hoping someone is Tweeting this out now, or nobody will see it.

This is a bit of a segue into the next segment, but what TV shows are you watching right now?

I do watch a lot of Quality TV, as the Quality TV-makers insist we call it. (How’d they arrange that? Can we call our Substacks “Quality Substacks,” thus suggesting they’re good, even if they blow?). Shows I’ve loved in the last couple of years? A partial list: Bill Hader’s Barry (the best show about a contract killer/community-theatre actor that’s ever been conceived), Ricky Gervais’s After Life (a brilliant, sad, and funny show, about a widower newspaperman), Succession (sue me, I’m easy), Righteous Gemstones (love that one, even if Season 2 was way over the top, but I’m a Danny McBride fiend), Larry David’s Curb Your Enthusiasm (the best comedy still on the air after twentysomething years), Yellowstone (Kevin Costner’s back, and cranky as hell!), Ted Lasso (I didn’t think I liked feel-good soccer shows or Jason Sudeikis, who knew?) and I even like The Morning Show because a feisty Reese Witherspoon sets my heart aflutter, plus, Billy Crudup has always been an underrated actor, and does some of his finest work here.

Before going into Glengarry Glen Ross, have you seen any of David Mamet’s work and given that his politics have become more dogmatic (he supported Donald Trump AND believed that the election was stolen), would you be comfortable having him on your side?

Yeah, I’ve seen plenty of his other films (many adapted from his plays). House of Games – I adore that film - almost made me want to become a professional conman. Instead, I became a journalist, which is pretty close. Mamet is responsible for many other things I love, or at least like a lot: Things Change, Homicide, The Spanish Prisoner. But Glengarry Glen Ross – also adapted from his play – is far and away my favorite. In fact, it’s definitely in my Top 5 films of all time, and don’t ask me the others – besides Miller’s Crossing and Diner – because I don’t want to have to waste the rest of the day thinking about what gets the other two slots. Something by Scorsese has to make the cut, probably (maybe Goodfellas, maybe Raging Bull). And of course, they’d take your fly fisherman’s card away if you don’t say Robert Redford’s A River Runs Through it (which is, by the way, a near-perfect film that I never get tired of watching). Maybe Wes Anderson’s Rushmore or Royal Tenenbaums could come off the bench, or even steal a starter’s slot.

As a political commentator? Mamet’s a sad, overly-partisan hack. Sorry, but he is. I admire his contrarian instincts, mind you. Not easy to do in the entertainment sector. But he basically traded one bleating herd of gullible sheeple for another. I hate to tell people to stay in their lane, but he should have. In fact, I’ll make a deal with him: if he doesn’t crank out overheated, credulous, conspiratorial nonsense, I won’t crank out award-winning films and plays. Problem solved.

Mamet’s screenplay is the star of the film, you feel the cast is competing against its biting energy. Do you have any favourite lines and who brought the best performance in the film?

That’s a hard call or should be, because everyone came to play. It was a Dream Team situation. Genius at every turn. Jack Lemmon, Alan Arkin, Ed Harris – all three gave some of their finest performances. Alec Baldwin, with his “Always Be Closing/Set of Steak Knives” speech, was as good as he’s ever been, or will ever be. Even the more mild-mannered throwaways – the performances by Kevin Spacey and Jonathan Pryce – did exactly what they needed to do. But for my money, Al Pacino as Ricky Roma – that belongs on the Mt. Rushmore of acting performances. Just perfect in every way. There are so many Pacino performances I love, but none as much as this. (Godfathers I and II included.) His triumphant set piece, the soliloquy he delivers as the real-estate hustler trying to reel in a mark (played by Pryce), is a sublime marriage of acting and writing at their best.

Rewatching the film, there are some truths to be had about the corporate environment. We all know it is cut-throat, but you feel a sense of desperation once the stakes are pushed to eleven. Jack Lemmon’s Shelley Levene was by far my favourite character. He’s sympathetic enough that by the time we realize he pulled off the robbery at the end, we realize that he seems relatively weak once he is up to the challenge, compared to his colleagues, because he’s set up with the worst leads. Beneath all the profanity, you’ll find a tragic film, with salesmen being emasculated, and becoming more suspicious of the firm’s management that they eventually quit. What did Mamet capture about working in an office?

So you’re a Machine Levene guy, I’m a Ricky Roma guy. It’s like Beatles vs. Stones, but I get why you loved Lemmon. He was brilliant. What Mamet captured about the corporate environment is how ruthlessly Darwinian it is. In order to succeed in this environment, you have to subvert your humanity. Yet in order to be good at your job, you have to be in touch with it. To part people from their money, you have to think and talk like them just enough to cut their throats. (Hey, it really is like journalism!) It’s kind of like the old Roger Stone line on politics: “Unless you can fake sincerity, you’ll get nowhere in this business.”

At the same time, you’re right, it’s tragic. You get the sense everyone is doomed – even the “success” stories – and this life, this art of deception they’ve chosen to excel at, isn’t sustainable. Ricky Gervais mined this in other ways, to comic effect, in the original British version of The Office, and the American version did much the same. Except the deception was mostly self-deception: that their lives weren’t as sad and empty as they actually were. The stuff of great comedy!

Let’s talk about Kevin Spacey. He has been in exile after being caught as a groomer, though we sometimes see him trolling everyone with his Christmas videos. While that smug, domineering schtick does wear off upon hearing that news and that it is often the kind of thing that he’s been known for, Spacey is perfect as the office manager, John Williamson. His weakness is in losing control of the salesmen since he believes he has enough power granted by management by refraining from having a say in the operations. But there are two things that caught me with Williamson: the way he has caught Levene in the act, making him so desperate, and that he is berated by Al Pacino’s Ricky Roma, who is the least ethical salesman in the building. Both of these characters, from opposite ends of the spectrum, have different opinions of the management but their job performances could not be more different. Yet throughout the film, Spacey is more low-key than what I would come to expect from him. Is that fair to say?

Yes, he wasn’t his full Kevin Spacey-self. The scenery-chewer he later became, much like Pacino has always been. But it’s what the part called for. And he played the perfect foil for Pacino, serving as the soulless corporate clock-watcher who just doesn’t get it. Who needs to be despised. (That last bit being good practice for what later happened to Spacey in real life.) Whereas Pacino embodied the honor-among-thieves ethos. One of my favorite lines comes from his berating Spacey’s character, in his disappointment with John Williamson bunging up a sale: “Jag-off John opens his mouth, blows my Cadillac. I swear, it is not a world of men.”

You said that the 90s was the last time cinema was at the height of artistic creativity, and certainly, Glengarry Glen Ross is part of that pantheon. Have you given up on the fact that movies won’t permit to the kind of storytelling demands that you want?

Well, to give you an idea, I used to physically go to the movies about 25-30 times a year. Now I’m probably down to about two, if I’m lucky. I’d rather stay home and watch good documentaries. Ross Douthat, in the New York Times, actually illustrated the how and why of this more fully than I could. And he’s nearly a decade younger than me, so it made me feel validated that he similarly located the 90s as being right around the time of film’s twilight glow, as he called it. That’s not to say that good films don’t still get made amidst all the tent-pole cape’n’codpiece dross. They do. But studio types have so successfully chased the real talent to smaller screens, where they can actually air out their stories in a more novelistic fashion than in a two-hour shot at the multiplex, aside from all the other pressing market forces (like the pandemic), the industry let a lot of the air out of their own tires. Not unlike the media industry unwittingly chasing so many of their stalwarts off, the latter of whom are now doing their stuff elsewhere as independents. Like on Substack. The parallels are striking. There ain’t a lot of Tom Wolfe’s anymore. Of course, there never were. But even if a young Tom Wolfe still stalked the earth, what would they do with him now? Probably put him in a cubicle and tell him to write three pieces of clickbait per day. As Ricky Roma said, it is no longer a world of men. And not just because half of them are changing their pronouns.