Film Club: Matt Johnson / Chinatown (1974)

The author of How Hitchens Can Save The Left talks about his book and all things Christopher Hitchens, before diving into Roman Polanski's neo-noir classic.

Welcome to the Lack of Taste Film Club, where we talk to non-cinephiles and non-professional cinephiles about themselves and the movies they love. You will find a different flavour to Film Club entries going forward. Instead of discussing the chosen movie, we want to get to know the guest more. A general Q&A will come first, and the film will come second.

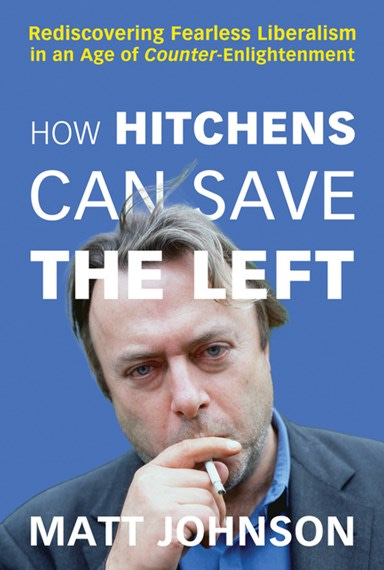

Matt Johnson is the author of How Hitchens Can Save the Left: Rediscovering Fearless Liberalism in an Age of Counter-Enlightenment, a biography of Christopher Hitchens and his complex politics. I was interested in the book, as well as the legacy that Christopher Hitchens left, following his death in 2011. We talk about his positions, including his support of the Iraq War, speculating his opinions had he not died, before going into Roman Polanski’s Chinatown, one of Matt’s favorite movies.

This is the public version of our conversation, while another version is for subscribers. Over there, Johnson and I talk more in depth about Hitchens, including his relationship with Tucker Carlson, and his most controversial opinion. If you would like to read this, please become a subscriber. It definitely helps.

Christopher Hitchens is beloved by many, but remains divisive within left-wing circles, particularly with his support of the Iraq War and his distancing from socialism. I'm aware that he's a polemicist who hit certain nerves whenever he criticizes religion as a concept, among other things. But if a reader who happens to be sceptical of Hitchens has your book in their hands, how will you persuade them, that he still held and practised some beliefs they share?

That would depend on the belief in question. Although my book is aimed at the left, many of Hitchens’s essential principles aren’t confined to a specific point on the political continuum. He always valued principles over politics – he cared about how people thought rather than the positions they happened to hold. If there’s a single overarching theme of the book – and one that may appeal to readers on the left and right – it’s the importance of universalism. From Hitchens’s contempt for religion, nationalism, and identity politics to his view that the United States should use its power to secure human rights abroad, universalism underpinned his most important and controversial arguments.

What are the arguments that he made in favour of the Iraq War, in comparison with the neoconservatives making the case to land there?

Although Hitchens was often wrong about Iraq, he supported the war because he knew Saddam Hussein was a cruel and erratic tyrant who presided over what the Iraqi dissident Kanan Makiya aptly described as a “republic of fear.” Hitchens argued that the United States should have removed Hussein following the Gulf War, which took place just a few years after his insane eight-year war on Iran and the genocidal Anfal campaign against the Kurds. Throughout the 1990s, Iraq’s economy imploded and Hussein became increasingly unhinged, threatening to invade Kuwait again, continuing to menace the Kurds, and becoming increasingly detached from reality behind his impenetrable security apparatus.

Hitchens believed this status quo would ultimately break down and lead to what he described as a “Rwanda or a Congo on the Gulf.” He thought state collapse was inevitable in Iraq, so the United States should get involved at the earliest opportunity. He made the case that Iraq’s sovereignty was already “at an end,” as NATO aircraft were patrolling significant swaths of its airspace to protect vulnerable populations such as the Kurds in the north and the Shia in the south. Hitchens also believed the only way to “certify” that Iraq was disarmed of WMD was to invade and take a look around, which was one of his weaker arguments (as it implies that nonproliferation efforts in recalcitrant states are pretty much pointless, despite the robust inspections regime in Iraq after the Gulf War).

But Hitchens was right that Iraq was an unstable totalitarian nightmare, and this was always at the center of his case for war. Many neoconservatives (such as Paul Wolfowitz, who had been making similar arguments for many years) agreed, though others were more focused on putting the United States in a stronger strategic position in the Middle East and exercising American power for its own sake. While some neoconservatives were concerned with the rights of Iraqis and the reconstruction of their society, others were just eager to topple Hussein and turn the country over to a friendly custodian government as quickly as possible (which is one of the reasons early investments in the war were insufficient and projections about its length and ferocity were so inaccurate). There’s no general neoconservative position on Iraq – to understand the diversity of opinion among the neocons, I’d recommend George Packer’s 2005 book The Assassin’s Gate: America in Iraq.

There’s an interesting interview with Hitchens in January 2001 in which he observes that Hussein is “everything that is said about him,” emphasizes horrors like the chemical massacre of Kurds in Halabja, and points out that Hussein could have the sanctions lifted immediately if he would stop behaving like an international pariah. This was when Hitchens was promoting The Trial of Henry Kissinger months before the September 11 attacks, which is a reminder that he was always concerned about human rights in Iraq – and that his support for the war was a clear extension of this concern.

Christopher Hitchens had a complex relationship with conservatives. His brother, Peter Hitchens, is a conservative commentator through and through. Sometimes he mocks a lot of their snobbery, while he would form alliances whenever there's an issue that became important to him. Because of the former, I don't think conservatives will take him on as one of their own. What does he have to say about making political alliances, even when they are in their nature, short-term and can be maintained through one issue and nothing else?

Despite the ways his politics intersected with the right, Hitchens always insisted that he wasn’t a “conservative of any kind,” so he certainly wouldn’t have cared whether conservatives accepted him as one of their own or not. But as you note, his relationship with the right was complex. When he “effectively” voted for Thatcher by withholding his vote from Labour in 1979, he did so because he believed the “closing years of ‘Old Labour’ in Britain were years laced with corruption, cynicism, emollience, and drift.” He thought Labour had become a “status quo party” that defended corrupt trade unions and expressed hostility to what he regarded as progressive causes – such as the integration with Europe.

Hitchens argued that the “radical conservative is not a contradiction in terms.” He emphasized Orwell’s embrace of conservative values and cited Lionel Trilling’s observation that Orwell seems to have thought that these values “might come in handy as revolutionary virtues.” He admired his brother’s convictions, despite their political disagreements. And he recognized the value of the conservative critique of radical excesses – for example, he described Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France as the “first serious argument that revolutions devour their own children and turn into their opposites.”

When I talk to people who love reading and watching Hitchens, they have an idea of a man with a fairly lavish lifestyle. He reads a lot, speaks and writes so eloquently, and during these cocktail parties in America’s capital, he drinks and smokes like a madman. That's how I felt when I first read his work, particularly Letters to a Contrarian. But the current circumstances of journalism are dramatically different and such a fantasy is less likely to persist. What would he say about being a journalist back then, and if a young person said he wants to be the next Hitchens, what would he tell them?

Hitchens told young journalists that writing should feel like a compulsion – like something they absolutely had to do. He said this conviction would help them through the inevitable disappointments, which (as you note) may be even more plentiful today. He also emphasized the rewards of having a “lived life instead of a career” (in the words of the Hungarian dissident George Konrad), which to Hitchens meant working independently and speaking honestly.

Hitchens urged writers to avoid becoming “party-liners” and to resist the demand for in-group loyalty – no matter the group. The theme of his essay collection Unacknowledged Legislation: Writers in the Public Sphere is the idea that individual writers who were willing to challenge cultural and political dogmas have often secured the most significant moral advances throughout history, such as abolitionism. While my book is directed at the left, Hitchens’s heterodoxy was a defining characteristic of his work and one of the main reasons he remains relevant today. At a time when so many writers work for mindlessly partisan outlets and increasingly find themselves captured by their own audiences and political tribes, Hitchens’s example of independent thought has never been more valuable.

Does it annoy you that Henry Kissinger, one of his biggest targets, will live long enough to become a centenarian?

It certainly would have annoyed Hitchens, who probably had Kissinger’s obituary written and filed away in an easy-to-reach place decades ago.

Since this is a newsletter about all things movies, Hitchens has written only two things about cinema: The Passion of the Christ, speaking about how much he hated what Mel Gibson wrought, and Master and Commander, which he found to be historically inaccurate. Did he write more about this area?

Hitchens actually wrote about cinema a bit more extensively than that. While it may not have been his favourite film, Hitchens often wrote about the dramatic impact Gilberto Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1966) had on him. He first saw it at a “volunteer work camp” in Cuba and described the experience as “shattering” and “electrifying”: “I went to the screening not knowing what to expect and was so mesmerized that when it was over I sat there until they showed it again.” Hitchens was particularly impressed that no actual newsreel footage was used in the film, which had the look and feel of a documentary. In his memoir, he writes that he was “completely unaware as were many first-time viewers that the harsh, grainy sequences of street fighting were not taken from a documentary, and near-intoxicated (despite my supposedly better ideological training) by the visceral, sordid romance of the urban guerrilla.”

Hitchens also described Monty Python's Life of Brian as one of the funniest and most intelligent films ever made.

So can you tell me why did you pick Chinatown?

I’ve always loved film noir, and Chinatown is the greatest example – the culmination, really – of the genre. It retains all the aesthetic power of the vintage noir from decades earlier without surrendering to the conventions that made many of those films so easy to parody.

For example, Jack Nicholson’s performance as Jake Gittes is appropriately “hardboiled” (a word that seems obligatory in just about every piece of writing about noir), but it’s also understated and ironic. This was a breakout period for Nicholson – Chinatown was immediately followed by One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in 1975, and The Shining was released a few years later in 1980. But I think Chinatown is his finest performance – from his effortless sardonicism to his wry and wary grin, noir is a natural fit. Nicholson may have the most iconic smile in Hollywood – the notorious still image from The Shining is his psychotic beaming face breaking through the bathroom door, and it’s no wonder that he was selected to play the Joker in Tim Burton’s Batman (1989). But in Chinatown, his smile isn’t mad or malevolent so much as cunning and suggestive.

It’s difficult to think of a film more saturated in a feeling of dread and foreboding than Chinatown. Jerry Goldsmith’s score flits from the melancholy wail of trumpet solos to eerie and dissonant strings and piano as Gittes unravels the two dark mysteries at the heart of the film. As with most great noirs, a brutal and seedy story steadily sinks into an even darker one below the surface. Noah Cross (played by John Huston) is exposed as the portrait of greed and cruelty when we discover that he’s willing to divert water from desperate farmers and kill public officials in a scheme to buy and develop land. Then we see the depravity he’s truly guilty of (with haunting echoes of Polanski’s own behavior), and it makes murder and theft seem benign by comparison. When Gittes asks, “What can you buy that you can’t already afford?” Cross says, “The future.” There’s something horrifyingly salient about that comment, given how Cross destroyed and stole his own daughter’s future.

Every element of Chinatown is close to perfect: the performances, the direction, the music, the atmosphere, and the story. I’ve probably watched it over a dozen times, and I’m incapable of starting it without watching it to the end. When the journalist Tom Burke saw an early version of the film, he realized that he had to use the restroom shortly after it began but found himself unable to pause the screening. I can relate. It’s as if Polanski and Towne learned every lesson about what to do – and not to do – from the entire history of noir and poured it into a single masterpiece.

This was the film that put Roman Polanski onto the cultural map (putting the pedophilia aside), and it has one of the greatest screenplays from Robert Towne. Is there anything that stood out to you in both the direction and the script?

One of my favorite things about Chinatown is the way it diverges from many noir tropes. Evelyn Mulwray is the “femme fatale” brilliantly played by Faye Dunaway, but she isn’t a manipulative temptress – she’s a decent human being with a horrible secret. Hardboiled and cynical as he is, Gittes also has sudden flashes of moral indignation. When he’s accused of doing disreputable work, he barks: “I make an honest living. People don’t come to me unless they’re miserable and I help ‘em out of a bad situation.” Gittes often implies that he doesn’t really care what happens in the world and only wants to protect himself, get paid, etc., but it’s never convincing.

All Gittes genuinely cares about is the truth, despite how hideous it turns out to be. The use of symbolism in Chinatown is sometimes a little on the nose, but that’s by design. After a henchman (played by Polanski) slices Gittes’s nostril with a switchblade, he spends most of the film with a bandage on the wound and the still-fresh gash is clearly visible at the end. Gittes’s nose is a fundamental motif – a reminder of the risks of seeking the truth, as well as the fact that he’s willing to accept that risk again and again. When a man Gittes interrogates ominously tells him to be more careful and says the wound must hurt, Gittes responds: “Only when I breathe.” When Gittes accuses Evelyn of hiding something and says her husband Hollis (the public servant who's killed by Cross, his former partner) was murdered, he says he doesn’t mind the cover-up. He claims to be interested in solving the case merely because he’s personally involved, and he emphasizes the symbol of this involvement: “But Mrs. Mulwray, I goddamn near lost my nose. And I like it. I like breathing through it.”

This is the amoral bravado of a typical noir antihero, but we know there’s more to Gittes than self-concern and greed (Evelyn and Cross both offer to pay significant sums of money for his services). After Gittes is attacked yet again and Evelyn saves his life, they end up at her home. When he removes the bandage, she’s startled by the seriousness of the wound – a stark reminder that he’s sacrificing his own safety to unravel a convoluted and ugly story that revolves around her (a story she's lying about). As Evelyn applies peroxide to the cut, Gittes notices “something black in the green part of your eye,” which she explains is a “flaw in the iris … a sort of birthmark.” The symbolism here is every bit as important as Gittes’s nose – Evelyn has seen the darkest side of human behavior, while Gittes is ignorant of just how dark this story will get. Chinatown is about seeing things and failing to see them. “Most people,” Cross tells Gittes after he’s uncovered his monstrous secret, “never have to face the fact that at the right time and the right place, they’re capable of anything.” The clue that exposes Cross is a pair of bifocals he dropped when he murdered Hollis. When Evelyn is killed during the dramatic final shootout in Chinatown, the bullet exits through her eye.

Finally, there’s the title motif. “Chinatown” is mentioned several times in the film – we find out that Gittes worked there with the detective investigating Hollis's murder (Lou Escobar, played by Perry Lopez). When Cross warns Gittes, “You may think you know what you’re dealing with, but believe me, you don’t,” he laughs and says that’s what the D.A. used to tell him about Chinatown. When Evelyn asks what he did in Chinatown, Gittes says, “As little as possible.” She responds: “The District Attorney gives his men advice like that?” and he says: “They do in Chinatown.” We then discover that something traumatic happened in Chinatown: “I was trying to keep someone from being hurt,” Gittes cryptically recalls, “I ended up making sure that she was hurt.” After Evelyn is killed in Chinatown, Gittes is staring at her body in a trance-like state and he repeats the words “As little as possible.”

As Evelyn and Gittes lie (in both senses of that word) next to each other in bed, he tells her that what happened in Chinatown was “just bad luck.” When she asks what he means, he says, “You can’t always tell what’s going on – like with you.” Chinatown is a film about inevitability – of unforeseen consequences for your actions, of the past’s intrusions on the present, and ultimately of human wickedness and our persistent, naive failure to understand it. Bad luck is just part of the story, but it’s the part Gittes focuses on to stay sane.

Would you ever classify this as a neo-noir, even though it's set near the 1930s and in Los Angeles as any other typical noir?

In a strong field, I’d describe Chinatown as the quintessential L.A. film. Beyond the genius of the production design and cinematography, which give us an evocative and intimate look at pre-war Los Angeles during a period of rapid growth, decadence, and corruption (this was a few years after the Hays Code restrictions were lifted, and the filmmakers took full advantage of this fact), the city is an integral part of the story. “Los Angeles is a desert community,” the mayor tells concerned citizens near the beginning of the film. “Beneath this building, beneath every street, there's a desert. Without water the dust will rise up and cover us as though we'd never existed.” The idea of L.A. as a city at the mercy of the natural world – as a sort of rickety facade permanently perched on the edge of destruction – strikes me as a powerful metaphor and fitting backdrop for the story. Again, it’s this idea of inevitability: no matter what we build, the desert is always waiting underneath, prepared to swallow us. No matter what Gittes does to deny, forget, or resist it, the reality of evil as a self-determining force in the world is inescapable.

Describing Chinatown as “neo-noir” seems reasonable, and there’s a seemingly inconsequential scene that makes a case for this classification. After Gittes informs a hapless client that his wife is cheating on him at the beginning of the film, the man walks over to the window and grabs the blinds in a fit of despair. “Alright Curly, enough’s enough,” Gittes says. “You can’t eat the Venetian blinds, I just had them installed on Wednesday.” Venetian blinds are a ubiquitous visual cue in the genre – they often cast ominous shadows from street lamps or moonlight outside, and these images are usually symbolic. In this case, there are no shadows – the Los Angeles sun is shining and the story hasn’t even begun. It’s almost as if Polanski and Towne are embracing the film’s cinematic tradition with this acknowledgment, while simultaneously telling the audience that what they’re about to witness isn’t “typical noir.”

How do you interpret the ending and do you think it was the right call for Evelyn to die? Cos in another ending, the good guys are supposed to triumph, but was changed as Polanski and Towne had a massive dispute about it.

I don’t have mixed feelings about the ending, and I can’t imagine why there was any dispute. If Evelyn had escaped with Katherine and Gittes had joined them in Mexico, it would have undermined the core themes of the film: tragic inevitability, the cost of taking action in a radically uncertain world, the bedrock reality of human depravity.

There was a similar dispute over the ending of Carol Reed and Graham Greene’s classic 1949 noir The Third Man. Greene wanted a happy resolution in which the main character (Holly Martins, played by Joseph Cotten) finally earned the love and affection of Anna Schmidt (Alida Valli). Schmidt was in love with Holly's friend Harry Lime (Orson Welles), despite the appalling crimes he committed and his psychotic lack of concern for human suffering. The film is a bleak masterpiece about greed, inhumanity, and doomed love and friendship, and it would have been ruined if Martins and Schmidt merrily strolled away together at the end. Instead, the final scene is one of the most iconic in the history of cinema: Martins waits for Schmidt on the side of the road after Lime’s funeral, and she walks past without even looking at him. Greene later admitted that Reed was “triumphantly right” to end the film as he did.

The most famous line in Chinatown comes at the very end – when Gittes takes one final look back at Evelyn’s body, his associate says, “Forget it, Jake, it’s Chinatown.” What would he say in an alternative happy ending? “See that, Jake? Chinatown isn’t all bad!” It would have been beyond parody.

Have you seen its sequel The Two Jakes yet?

I haven’t. Perhaps I’m afraid to watch it. Chinatown is such a singular and cohesive film – I’m surprised it was originally conceived as a trilogy.