Film Club - Jasmine Hu-Hollingshead / The Wedding Banquet (1993)

The College Fellow at the UVA talks about how people talk about pop culture depictions of mental health, the state of Asian-American cinema, before diving in on one of Ang Lee's most charming films.

Welcome to the Lack of Taste Film Club, where we talk to non-cinephiles and cinephiles about themselves and the movies they love. You will find a different flavour to Film Club entries going forward. Instead of going straight to discussing the movie being chosen, we want to get to know the guest more. A general Q&A will come first, and the movie comes second.

In this edition, Jasmine Hu-Hollingshead is a guest who is not a household name, compared to other guests that I had. She’s a teacher at the University of Virginia, but she wrote one of the most provocative essays on current popular culture I have read all year. The essay, published in Quillette, and titled Art is Not Therapy, is about what it says in the headline, detailing the flawed approach of mental health within film and TV, primarily Turning Red and Everything Everywhere All At Once, two critical darlings that are supposed to speak for the Asian American experience. You should give it a read before this Film Club begins.

We talked about why she wrote the essay, the artist playing surrogate for the therapist experience, and the problems with modern Asian American cinema. We then dive into The Wedding Banquet, a queer rom-com from Ang Lee, that strikes a sweet spot of the immigrant experience that most films of that genre haven’t achieved.

So what made you write that essay about art and how it substituted into therapy?

I had noticed the encroachment of therapeutic language into the evaluation of media for a while. And then the two films Turning Red and Everything Everywhere came out and the discourse around them was so similar— they’re cathartic, they’re healing intergenerational trauma, they’re particularly meaningful to the Asian diaspora but also full of universal human truths, all this dreary rhapsodizing about socially conscious messaging. There were even assertions that the films themselves were good because of their therapeutic value.

I don’t even hate the two movies— I think they’re corny and aesthetically bankrupt but typical Hollywood fare. It was more the way in which critics marched in lockstep, taking on this profound, grandiose tone as if they were groundbreaking masterpieces when they were just silly family films. Imagine if the entire critical apparatus claimed The Nutty Professor was cathartic and healed intergenerational trauma! You would feel taken for a ride!

But for a good while, after my article came out, I had people sending me impassioned Notes app defences of Everything Everywhere. Nice, cool, I don’t care!

Just out of curiosity, did you get any backlash specifically because it was written on Quillette, which is deemed controversial by some academics? I think you are the first person I know who has a byline at that magazine, while also being an author of Symmetry, Violence, and The Handmaiden's Queer Colonial Intimacies?

No, no backlash, I'm too lowly. I think academics are largely unaware of other people's lives and work unless they're, like, superstars.

There's a normative mantra I've heard about art which is that it's supposed to be a mere reflection of society, rather than a way of practising new ways in exercising your own psyche. When you explore the reactions to Turning Red and Everything Everywhere All At Once, it feels like they are memories that are very precious to the viewer and there's a profound emotion of having your experiences overlap and match with the artist’s. But as you've written in that essay, there's a lack of humility that would allow some to overcome many obstacles.

There’s definitely a natural sense of nostalgia animating both: as my generation of Asian Americans reaches adulthood, they’re reflecting on their childhoods.

But if you look at the way these films treat personal memory, it’s always simplified and smoothed over in a way that aligns with the dominant American identity discourse. There’s a hyper-individualist, hyper-verbal focus on acceptance, acknowledgement, and validation that doesn’t grasp the complexity of human relations. The moms always end up giving heartfelt, very verbal apologies. Actual Asian parents would rather die than say this stuff, just to spite you. It’s part of their charm! And their strength as parents— I’d bet these filmmakers wouldn’t be the successes they are today if their parents were like permissive, huggy kissy white boomer parents.

Even little details like the boy band in Turning Red clearly being based on the Backstreet Boys or N*Sync, but they’re instead turned into a racially diverse group with K-pop-type members. It’s taking something that would feel real and lodged in memory and sanitizing it into something that never existed because they’re uncomfortable with something as innocuous as Asian-American tween girls having crushes on white boys. As a result, it can’t really resonate as personal or real to anyone. The 90s Toronto setting in Turning Red feels totally synthetic; everyone’s styled like TikTok zoomers referencing the 90s, not actual 90s kids.

Probably the most famous on-screen depiction of therapy being practised is The Sopranos, which I think is increased in popularity because someone needs to find something to watch during the pandemic, but also because it speaks about mental health in a way that you don't usually expect it in a character like Tony Soprano, who is brash and prone to losing his temper. But we learn to understand him, because of his upbringing by his mother, who is based on David Chase’s experiences of his own upbringing. Presuming that you have seen The Sopranos, is that the best way to view a show like this?

The humour of The Sopranos’ conceit, of a mobster going to talk therapy, is probably lost on our therapeutic generation. It’s clear that we’re supposed to find this tough guy with masculine, Old World values having panic attacks and going to this Crate and Barrel yuppie lady therapist very funny. But nowadays in my classes, every time a character does something mildly “problematic” and thirty zoomers will chorus “Empathy problems! Go to therapy!” So it’s not really a good joke anymore, it’s such a prevalent attitude.

The Sopranos is at its heart an immigrant story about American assimilation and the inevitable loss of an entire way of life. Therapy’s creep into Tony’s worldview is an effective way to show that loss. For earlier generations, abuse like Livia’s was the normal way that boys were initiated into adulthood and masculine violence— not good, of course, but not pathological— but Melfi’s therapy translates it into a new existential language. It’s a really ambivalent, even-handed depiction of therapy. When Melfi is an effective therapist, she actually makes Tony a better mobster, and more effective at violence— because curing depression is about curing inaction.

One of my favourite moments is when it’s revealed that all the Sopranos have therapists, including Janice, whose hippie therapist believes that God is a woman who twerks marvellously or something, and tells her to “show some of that compassion she’s famous for.” There’s something so funny about everyone in this family, even Janice, having their own therapist gassing them up and validating all their private narcissistic impulses!

I was wondering if you have any thoughts on Bojack Horseman because it has almost evoked the same reaction as all of the pop cultures that I've mentioned; a critically acclaimed show depicts a flawed and mentally unstable protagonist, and we feel for him when he performs at his very lowest. Personally, I thought it was brilliant up to Season 4 and afterwards declined into mediocrity once it is more interested in diagnosing him as a terrible human being who got his just desserts by the end and doubling down on everything that we've already seen before. Doesn't that have the effect of harming the person who possesses these similar experiences watching it than being open to them?

I didn’t watch Bojack. But there is absolutely a trend from millennial media onwards that slaps on a morally didactic diagnosis like “of course, he’s a trash person, that’s the point” for its viewer. Oftentimes this serves as a cover for audiences to indulge in the dark or problematic aspects of the character— in Breaking Bad you have these moralizing voices scattered throughout reminding you of Walt’s cruelty and selfishness, but let’s not pretend that watching this character’s descent into Heisenberg isn’t the fun of the show!

This trend of needing explicit disclaimers, even if it contradicts the libidinal drive of the narrative itself, shows that we’ve gotten really uncomfortable with people coming to their own moral conclusions, or simply presenting a story without needing to drive home a message. And yes, I think you’re right— it also means we’re uncomfortable with our own dark sides. We can’t accept our internal Bojack or Heisenberg — we want a moral arbiter in our ear at all times.

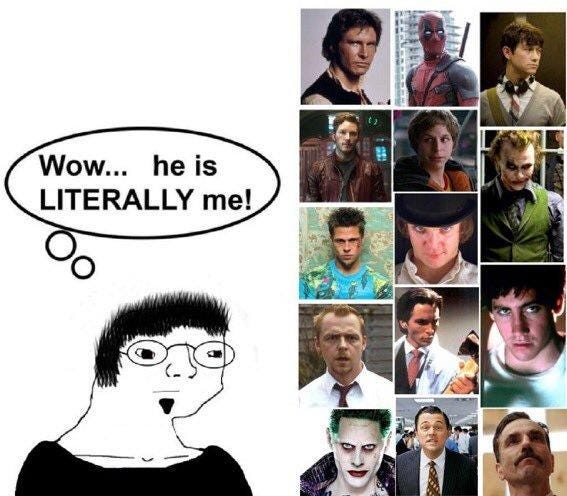

There is a meme in which the viewer watches a TV show or movie and utters "wow, he's literally me." These are usually characters - male and female - who feel alienated and isolated that they become more sociopathic, as a retaliation to the rot and conformity of their surroundings. Bojack Horseman, Tony Soprano, the Joker, Patrick Bateman, Travis Bickle, or Amy Dunne come to mind as those fitting that kind of mould. I find the trope interesting because they give an idea of how masculinity has evolved for these people. Not in the sense that they are being the purest wholesome male role model, but the complete opposite; memories in which hopelessness and nihilism occupy the mind that they lash out as a way to look for meaning. As you suggested, we're not allowed to indulge in their woes, according to some folks, unless you play the moral arbiter, and there's a counter-meme that says "you missed the point by emulating the narrator from Fight Club", to signal that these works have made it explicitly clear that these are flawed people. Nothing more, nothing less. I mention Amy Dunne as another Literally Me character, but I think she is the feminine version, in that her goal is to point out the invalidity of men and the patriarchy. Women aren't condescended to that way compared to their male counterparts. For the record, I personally do not know anyone who is male idolizing any of them, and at most, they understand how bleak their situation and why they made existentially bad choices. Connecting to your thesis about art and therapy, do you see that as a double-edged sword?

You mean, are antisocial, nihilistic characters potentially dangerous because unstable men might identify with them? I think people identify with fictional characters because they can't actualize those sides of themselves in real life. The characters are resonant because they speak to one's "Shadow Self." The feminine counterpart is often not Amy Dunne but Twilight-- women are probably more inclined to explore a shadow self through fictional romance. And in the last decade, with backlash over stuff like Fifty Shades, there's been a censorious push intent on labelling "toxic" fictional relationships in fandom and romance.

Could someone's identification with a fictional character exacerbate their mental illness? Maybe-- although I think real-life factors would almost always take precedence over fiction. But the backlash against "toxic" characters or relationships and the demand for morally "hygienic" narratives far exceeds any real-world repercussions. I think it's just become a cover for people to socially police each other. People also increasingly confuse moral judgments for critical perspicacity. There's this impulse to constantly offer judgments and nitpicky "takes" as a sign of one's intellect. No one trains their ability to just sit patiently with a piece of art while suspending cognition-- it's like they're all writing little video essays in their head.

The current wave of Asian-American cinema seems to specialize in the tensions between the family, and what I find striking is that it reaches the exact same conclusion: that we're uncomfortable with our parents, and they are uncomfortable with their parents as well. As you've mentioned Turning Red and Everything Everywhere All At Once focus on that, and so do The Farewell and Crazy Rich Asians. There's a meme that compares that with the storytelling of cinema in other Asian countries, which is far more diverse than that. Do you think that there is a potential for Asian Americans to expand their capabilities of expressing themselves beyond this trope?

Yes, I hope so! It’s not that Asian-American filmmakers shouldn’t explore family conflicts. Family is a rich, evergreen theme. It’s the way in which they sanitize their own culture and identities to be palatable to liberal sensibilities that I take issue with. They feel like college application essays.

Ultimately, the discomfort toward the family probably conceals a greater discomfort toward the self. I empathize. It’s hard to inherit a cultural lacuna and figure out who you are. But you can’t look towards this incredibly market-driven “Asian American” diaspora narrative where it’s all “grandmother’s weathered hands grasping a wooden bowl under the mango tree” to solve that. This cloying fantasy of the subtropical matriarchal homeland does not exist!

Luckily, the great blessing of being an immigrant is that you have a rich, foreign, secondary worldview to draw upon. Everything is so insular today, so it’s vital to read and watch stuff from another time, another place, another sensibility. It’s always telling that those who most bemoan a lack of Asian American stories also seem to be ignorant about the incredible richness of East Asian cinema.

There was a really terrible review of Turning Red in The AV Club, where the conclusion that the writer comes to is that it provides a 'welcome respite from anti-Asian hate?' On the one hand, it has everything I despise about cultural criticism, but even if it's a genuine expression of the author’s experience, there is a condition that for them to get published they have to chase a pre-determined narrative with the illusion of opening up the discourse. And I feel bad for the author if that is the case. Do you think the way that pop culture is categorized by critics into topics that correspond with fashionable trends - like mental health and representation - has some correlation with the low financial incentives that come with this genre of writing?

Definitely. The therapeutic and identitarian themes are convenient topics that everyone can latch onto. It immediately gives your work weight and levity— I’m not just telling a story about myself, I’m socially conscious!

This is the exact branding exercise I was taught in academia. Fit your work into topics like gender and sexuality, world literature, or medical humanities. As long as you connected enough of these little tags, you could be comprehensible and visible. Very important in an economically dire climate.

But the problem with this approach is that in the long run, you’re making yourself interchangeable and therefore irrelevant. Everyone can write a movie summary and slap on some identity and mental health themes— just like you can make a tweet about being a “hot girl who is depresso” and get 10k likes. It takes no particular insight or commitment to truth, so why would people listen to you over some other person saying the exact same thing at Slate, etc? Far better to be committed to your own vision.

The Wedding Banquet (1993)

So what made this film so special to you?

It’s such a sweet, good-natured movie that really understands the immigrant culture and the clash of worldviews between generations. It understands both sides.

I take issue with the current crop of Asian American filmmakers constantly erasing the past by asserting that, before their uniquely groundbreaking film, Asian American representation has never existed in Hollywood, or it’s only been Mickey Rooney Breakfast at Tiffany stereotypes. Here, from 1993, you have a wonderfully textured portrayal of a handsome Asian American gay man.

Also, I love Ang Lee! He’s sentimental and commercially successful, so I think film people forget how competent and interesting he is as a filmmaker. His films are so diverse but always beautiful, and there’s such a humanistic touch to them. I love Lust Caution, Brokeback Mountain, Sense and Sensibility, Crouching Tiger… I even like his Hulk— in this age of glossy prefab Marvel superhero nonsense that is 90% green screen, there’s something so poignant about the Hulk’s rubbery clumsiness.

Would you say it is Asian-American cinema or Taiwanese cinema because there is an overlap in tropes that are associated with both countries?

Its status as a joint venture between Hollywood and Taiwan’s film industry is probably why The Wedding Banquet feels so unique and fleshed out. The English and Mandarin dialogue is all really good.

This is part of Ang Lee's trilogy of films, where the father is basically the critique or focus of each film. What are some areas that The Wedding Banquet succeeds compared to Eat Drink Man Woman, which I liked even more?

I love Eat Drink Man Woman too: the dad getting his taste back so he can criticize his daughter's cooking-- peak Asian parent! The Wedding Banquet just has a personal element for me, having grown up in the US with conservative Chinese parents while wanting to get up to typical American kid hijinks. The sort of unspoken rules of interacting with your parents, in which you just propagate the most convenient fiction out of respect for them, is very real. You don’t engage them in torturous, emotional struggle sessions in which you ask for your “true self” to be “validated!” That’s for spoiled weaklings, ha!

it’s interesting there’s the “father knows best” theme whereas Turning Red and Everything Everywhere is about mommy issues and have these barely present, very cowed fathers. But Lee has much more sympathy towards patriarchal wisdom— a sign of mature vision.

How do you feel about the queer layer that paints The Wedding Banquet?

I thought it felt touching and real. Simon is in some ways the most decent, sympathetic character: the perfect Chinese daughter-in-law born in a white man’s body! Even though it’s a film about Asian American identity, and you get a sense of the loneliness of being an immigrant, you actually most feel Simon’s loneliness when he gets left out of these familial, cultural tableaus. There’s a real undercurrent of immigrant pride during the movie’s wedding— even though they’re so far from the homeland, these social practices and connections are still strong.

It depicts the struggle of being gay but no one is a caricature or unrealistically precious about their identities. Both Simon and Wai-Tung feel like real people— little details like when they hide away their copy of Todd Haynes’ Poison, or when Simon convinces Wai-Tung to go through with the scheme because of marriage tax breaks.

And the depiction of the parents’ Confucian perspective shows that it’s not as simple as “older generations are backwards and bigoted.” The parents’ primary objection to their son’s homosexuality is that he can’t continue the family line. It seems like liberal and conservatives today are uninterested in considering how it might be a loss for gay men to essentially be unable to have biological kids without paid surrogacy. The fact that the film actually makes reproduction a central problem and “solves” it in a traditional way is refreshing.

Is there any particular scene that stood out to you?

I love the wedding day itself. You can tell Lee loves the details of the pageantry — the portrait-taking and incredibly mannered, artificial poses, the guy in the kitchen carving the radish phoenixes, the endless flow of dishes coming out. I had a Chinese banquet wedding so it brings back happy but bemused memories. When Wai-Tung and Wei Wei enter the big banquet hall, there’s a very real feeling of “where did all these people come from?”